Building Android apps with Jenkins: an introduction

Why is mobile CI/CD special?

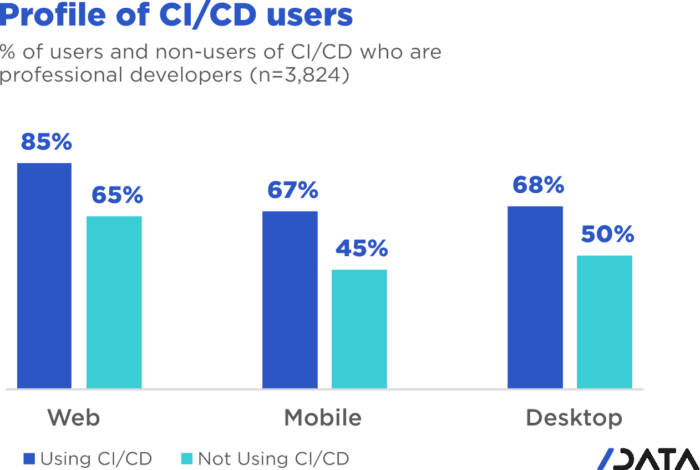

In 2020, a surprising 33% of professional mobile app developers were not using Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) practices, which is 18% more than web developers. There are several reasons why this is the case:

-

Unique needs: Unlike web applications, mobile applications have different requirements, which means that mobile CI/CD requires a different approach and dedicated tools.

-

Tightly controlled ecosystems: Unlike the open ecosystem of the web, mobile app ecosystems are tightly controlled by the OS providers, such as Apple and Google. These providers have strict rules from development to deployment, to running the apps. As a result, traditional CI/CD approaches and best practices can’t be applied out of the box.

-

Specialized expertise is required: Mobile CI/CD requires specific expertise that may not be available in the typical DevOps team. In many cases, mobile developers must handle the mobile CI/CD pipeline themselves due to the unique requirements. However, it is still CI/CD and requires that specific mindset, along with mobility knowledge.

-

Mobile CI/CD requires a separate pipeline: Mobile CI/CD requires setting up a separate pipeline from web or backend stacks, as it is based on the deployment of a compiled binary, which has to be installed on a mobile device from scratch every time. End-user deployments for B2C apps are subject to app reviews and app release waiting periods, which is not prevalent in other stacks. As a result, errors should be detected at the earliest stage (the famous "shift-left") and mobile-app-specific code analyses and tests should be incorporated at every step of CI/CD to avoid issues being discovered by the end-user.

-

Code-signing is mandatory: Unlike most other stacks, code-signing is mandatory in mobile app development. This introduces another layer of complexity on top of the already complex mobile CI/CD processes.

In summary, mobile app development requires unique CI/CD practices, due to the specific needs of the mobile app ecosystem, the specialized expertise required, and the need for a separate pipeline for deployment. By understanding and addressing these challenges, mobile app developers can successfully adopt CI/CD practices and ensure the delivery of high-quality mobile apps.

How do we progress then?

Mobile app development requires dedicated tools and approaches for CI/CD management. However, in many cases, mobile developers themselves are tasked with managing CI/CD, which is not their core role. This can result in significant time and productivity losses.

To optimize mobile CI/CD management, it is essential to have a dedicated team member who is knowledgeable in both mobile development and CI/CD. Ideally, this person would have experience as a former mobile app developer who has transitioned into a CI/CD role. Alternatively, someone who knows CI/CD and wants to help mobile app developers onboard the CI/CD train can also be valuable.

In conclusion, by having dedicated team members who are knowledgeable in both mobile development and CI/CD, and by utilizing effective tools and approaches, mobile CI/CD management can be optimized to improve productivity and minimize time losses.

Flashback to my previous job

At my previous job, we evolved our mobile CI/CD system over time and ended up using Gitlab-ci, along with a set of specific Docker images. Our standard image contained the latest version of all the required tools, including maven, ant, gradle, android SDK, android NDK, flutter, firebase, linters, and dependency checkers. This image was cached on the runners, similar to Jenkins agents, so that jobs could start immediately.

We also created specific images with various versions of the tools or with specific tools added. Additionally, we linked an Android Device Farm to Gitlab-ci, so that developers could test their newly built app on real Android devices directly from their pipeline.

In 2022, I resigned from my previous job and started working at CloudBees. Soon after, my manager asked if I would be interested in replicating some of the work I had done with GitLab-CI, but this time using Jenkins. I was intrigued and asked two questions. First, does Jenkins work well with Docker (to which I got an honest "sort of" answer), and second, whether I could start from scratch without looking at what had worked for Android app development with Jenkins previously. My goal was relying instead on my old GitLab habits, even if that meant failure. To my surprise, my manager said, "Go for it," and I began my journey to experiment, learn, and share my findings.

Given my more than 8 years of experience with Mobile App CI/CD, I initially thought this would be a cakewalk. But it turned out to be quite the ride…

Starting with Jenkins

I embarked on a new journey with Jenkins, despite having no prior experience with the tool. As a result, I made every mistake a Jenkins newbie could possibly make. To begin my learning process, I knew that starting with an empty Android application was the logical first step. However, as the saying goes, it’s difficult to teach an old monkey new tricks. Therefore, I decided to dive headfirst into rebuilding an Android Docker image, attempting to fit in all the tools I could think of, much like I had done previously with Gitlab.

In my naivete, I believed that once I pushed the image to DockerHub, Jenkins would somehow magically use it for my builds, and I would be done in a matter of days. Looking back, it’s almost endearing to see how naive I was. Simultaneously, I installed Jenkins through Docker on my Windows laptop and experimented with a few tutorials, starting with the simplest jobs possible that worked.

After successfully pushing my bulky Docker image, filled with all the necessary tools, I moved onto creating an empty Android application, with plans to connect the dots later on.

Android app

To start, I created a new repository on GitHub and cloned it onto my laptop. From there, I opened up Android Studio and created a brand new application from scratch within that folder. Once I had everything set up, I committed and pushed the app shell to GitHub.

To make sure the application could be built outside of my machine, I added a GitHub Action file. Thankfully, building a simple Android app is possible with GitHub Actions, as they provide Java and Android SDK in their Ubuntu:latest image.

With this setup, my empty app could be built on Android Studio and with GitHub Actions. As a result, I was able to obtain my APKs on both platforms. It was a satisfying milestone to achieve.

Following the official documentation, I managed to install both the Jenkins controller and agent. However, as a beginner, I found the process unnecessarily complex. Despite successfully running a Jenkins controller and agent on Docker images on my laptop, I encountered difficulties when trying to run my custom Android building Docker image on it.

Now I understand that there were other ways to approach the problem, but at the time, I was determined to stick with my old habits. I knew that creating a specific agent by starting with the SSH agent Docker image and adding the Android SDK was an option, but I was more comfortable using my custom Docker image and generic agents. As the saying goes, "when your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail".

The Free Tier parenthesis

Unfortunately, I ran into some issues with running my custom Docker image under Windows. So, I decided to create two Jenkins agents on Oracle Cloud Free Tier machines instead. I installed Java and Docker on these machines, and then created a Jenkins agent that was handled by systemd. This allowed me to continue working on my project and explore different ways of using Jenkins.

One of the Free Tier machines on Oracle Cloud was set up with the Android SDK so that it could handle Android jobs, earning it the moniker "JenkinsDroid". Using this machine, I created a simple Android job on Jenkins that referenced my GitHub repository and initiated the build process.

As I gained confidence, I added more checks and bundle creation, and soon found myself with a long list of build steps in a FreeStyle project. However, I realized that if the Jenkins controller were to restart for any reason, my current builds would be lost. This was a major drawback, and I wanted to find a more robust solution.

After some research, I discovered that pipeline jobs are not affected by the controller restart issue. As a result, I decided to switch to pipeline jobs to ensure that my builds would be safe even if the controller restarted.

From FreeStyle to Pipeline

As a developer, I often try to find ways to make my work easier. Admittedly, I can be a bit lazy when it comes to certain tasks. That’s why I decided to use the Declarative Pipeline Migration Assistant to convert my FreeStyle project into a Pipeline project. However, my first attempt at using this converted pipeline failed due to incorrect syntax. It was back to the drawing board for me, and I had to learn the Declarative Pipeline syntax. Remember the old Apple ads from around 2009, where the answer to every need was "there’s an app for that"? In the same way, Jenkins has a solution for almost every need. One thing I appreciate about Jenkins is that it offers a lot of flexibility regardless of the version being used.

Jenkins is an incredibly powerful tool, with a vast community contributing to its plugins. With over 2,000 plugins available, it’s safe to say that if you have a need, there’s likely a plugin that can help you achieve it. However, with so many options available, it can sometimes be overwhelming to choose the right one. It’s important to note that some plugins may be outdated or incompatible with your Java or Jenkins version, so it’s always wise to double-check compatibility before installing. Despite these potential challenges, the sheer number of available plugins is a testament to the versatility and flexibility of Jenkins.

To start with, I began with a small Pipeline description, gradually expanding it to incorporate more stages, additional tools, static analysis, compilation, unit testing, and ultimately, the creation of the release, which we will explore in a few weeks. However, the worst possible thing happened: I lost everything.

As previously mentioned, my Jenkins controller instance was running on my Windows machine, running atop Docker. One day, as I was trying to free up space for Android builds, I unintentionally entered a Docker command that removed all volumes, resulting in the loss of my jobs and their respective definitions.

Despite taking precautions, things can still go wrong. It was frustrating, but I learned from it and decided to store my Jenkinsfile in GitHub along with my other files, which gave me a sense of familiarity since GitLab-ci uses a similar approach. With Jenkins, I could create a separate Pipeline for each branch with different agents, different Docker images, and different tools, which was very convenient. However, it’s not perfect since a branch’s last commit/push is always used to start a job, and it’s impossible to build a specific branch explicitly.

Using a simple Pipeline with multi branches

Status

Let’s face it, unexpected issues can occur during a build.

While it is ideal to have everything reproducible at the click of a button, in the real world, a machine serving dependencies can go down, a link can break momentarily, or a docker image layer can go missing.

When using dockerfile: true, the risks are even higher, as you’re building the tool you’ll be using for the build, and sometimes things can go out of control.

When a build fails due to missing dependencies on Branch A, but a build on Branch B starts because it’s the latest commit/push, what can you do?

It’s not a good idea to keep a simple pipeline project when working with multiple branches.

That’s why I switched to a Multibranch Pipeline Project later on.

At this point, I had several branches, each with a Jenkinsfile. I also had Free Tier machines struggling to keep up with the heavy load.

Let’s make things a bit more complex

As I was testing different tools and stages using different Jenkinsfiles on various branches, I realized that using the same Docker image on all branches was not efficient. I started exploring the idea of using a different Docker image per branch, based on the specific tools or tool versions required. This made sense because using a generic Android image would result in additional download time during the build process for non-bundled tool versions.

Developers prioritize fast pipelines, and a custom Docker image with the correct tool versions is a way to achieve this. However, this custom image may not always be present in the Docker cache, resulting in slower builds.

To tackle this issue, I decided to automate the Docker image building process and use GitHub Actions to build and push the images to my Docker registry.

Of course, achieving a "fast" pipeline (around 5 minutes) depends heavily on the agent’s specificity. If it’s attached to only one project, then there’s hope that, even with various versions of the Docker image, the Docker cache would be large enough to ensure that builds fire up immediately.

To accomplish this, I had a potentially different Dockerfile per branch, and an image per branch, built using a GitHub Action and pushed to my Docker Hub repository. At that point, I had a working declarative pipeline for each branch, as well as a separate Docker image for each branch. Ultimately, this allowed me to generate an application binary that was ready to be deployed.

Ready? We’ll see that in the following blog post of this series.